To truly appreciate the sanctuary of a

modern bedroom, one must understand the long history of how we, as humans, have

sought to master the night. From the flickering firelight of ancient caves to

the gentle down duvet in today's bedroom, the materials we have used to wrap

ourselves in weave an unseen epic of survival, comfort, and craftsmanship. This

article will trace this journey, exploring how humanity progressed from mere

survival against the cold to the pursuit of the ultimate restorative art; why

certain natural materials have endured the test of time, while others have

quietly faded away.

1. Prologue: Humanity's "Thermal

Disadvantage" and the Eternal Quest for Warmth

When we look back at the history of human

development, we see a fascinating trade-off that has defined our species. From

the perspective of evolutionary biology, humans are quite unique among mammals.

Millions of years ago, our ancestors began to shed their thick, protective body

hair. This was a monumental shift that allowed us to gain superior cooling

efficiency. By being able to sweat more effectively across our skin, we became

incredible endurance runners, capable of moving for long distances in the sun

without overheating.

However, this biological advantage came with a significant "thermal disadvantage." We essentially traded our built-in insulating barrier for a cooling system. This transformation turned us into a species that is remarkably reliant on external means to fend off the cold. Unlike a bear or a wolf, we cannot simply rely on our own bodies to stay warm when the sun goes down or the seasons change.

This biological shift forged what is

perhaps humanity's most primitive and fundamental pursuit: the quest for

warmth. This wasn't just about comfort; it was a core requirement for survival.

In our earliest hominid days, this meant seeking out cave dwellings that could

trap the heat of the earth and mastering the use of fire to create a localized

micro-climate. As nascent

civilizations began to form, we looked to the natural world around us, using

animal skins and crude furs to create a portable shield against the wind and

snow.

Maintaining warmth has always been a

fundamental human need. Even today, in our modern world with central heating

and smart thermostats, that primal urge to feel "tucked in" and

protected from the ambient air is still wired into our DNA. We don't just sleep

to rest our muscles; we sleep to recover in an environment that feels safe and

thermally stable. When the temperature drops, our heart rate and metabolism

change; providing a stable layer of warmth allows the body to focus entirely on

deep recovery rather than burning energy to stay warm.

2. The "Trial and Error" of

Sleep Insulation Materials

As humans transitioned from wandering

hunters to settled farmers and city-builders, we began to experiment more

systematically with textiles. We moved away from heavy animal skins—which were

difficult to clean and stiff to move in—toward materials we could grow,

harvest, and weave. This started a long period of trial and error as we tried

to find the perfect sleep insulation.

The Agrarian Era and the Rise of Plant

Fibers

With the dawn of agriculture, cotton became

the most widespread filling for bedding across much of the world. It was a

massive step forward. Cotton was absorbent, relatively soft, and easy to

produce in large quantities. However, the limitations of cotton as a bedding

fill are well-documented throughout history. Cotton is fundamentally a

"flat" fiber. To keep a person warm during a harsh winter, you need

an incredible amount of it.

This resulted in quilts that were

incredibly heavy. For the elderly or those with joint pain, the weight of a

traditional cotton quilt can actually be quite uncomfortable, pressing down on

the chest and restricting movement. Furthermore, cotton is prone to clumping.

Over months of use, the fibers settle and mat together, leaving some parts of

the blanket thin and others lumpy. Once cotton loses its structure, its ability

to hold heat drops sharply. It also absorbs moisture but doesn't release it

quickly, meaning if you sweat at night, the cotton quilt stays damp and cold

until morning.

Wool was another major development.

Harvested from sheep, wool offered much better warmth than cotton and possessed

a natural ability to wick away some moisture. However, wool is rarely

"lightweight." It also has a tendency to retain natural oils and

odors, which can become more noticeable over time. For those with sensitive

skin, the coarse nature of wool fibers can cause irritation, making it less

than ideal for a luxury sleep environment.

The Industrial Revolution and the

Synthetic Wave

The invention of synthetic fibers, such as

polyester filling, was marketed as a revolution in the 19th and 20th centuries.

These materials were affordable, very easy to care for, and offered a solution

for people with severe natural allergies. However, as the world moved toward

these mass-produced options, we discovered inherent physical drawbacks.

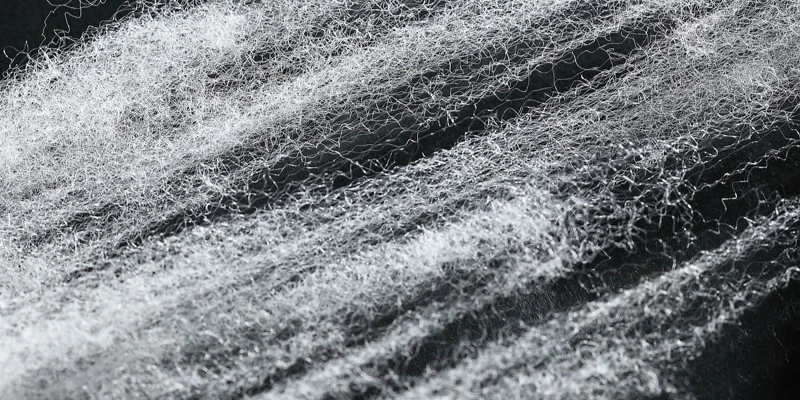

Synthetic fibers are essentially plastic.

They lack the complex, microscopic structures found in natural materials.

Because of this, they have very poor breathability. Most of us have had the

experience of waking up at 3:00 AM feeling both hot and cold at the same

time—your body heat is trapped, but so is your sweat. This creates a clammy,

humid environment under the covers. Furthermore, synthetics are known for generating

static electricity, which can disrupt a peaceful night's rest. These materials

rely on sheer "thickness" to provide warmth, leading to a bulky,

stifling feeling rather than a gentle embrace. They also tend to lose their

bounce quickly, becoming flat and useless after just a few years of use.

The Core Dilemma Emerges

Historically, the ideal sleep material has

always struggled to balance several key factors at once: thermal efficiency

(how much warmth you get per unit of thickness), weight, breathability,

durability, and skin comfort. For centuries, choosing a blanket meant making a

sacrifice. If you wanted to be warm, you had to accept the weight. If you

wanted something light, you had to accept being cold. The "perfect"

balance remained out of reach for a long time, as humans grappled with the

physical limits of plant and synthetic fibers.

Because there is so much to share, we have

divided this content into two parts. In the next chapter, we will look at how

nature finally provided the answer to our quest for warmth and how modern

technology has refined it. If you want to learn more about the secrets of the

near-perfect insulator,

please stay tuned for Part 2.